Tom Nyuma and the Making of the NPRC: In Memoriam to “Ranger” Part II

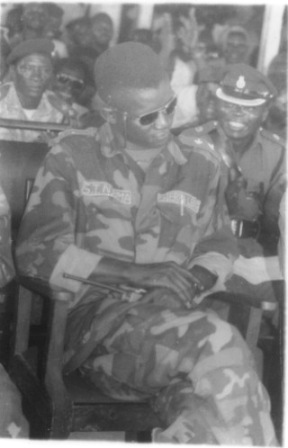

The circumstances that led to the April 29, 1992 coup started a day before, on April 28 when Tom, along with his fighting men, commandeered the AA gun, and embarked on a journey from Pujehun (around Zimmi where Tom was based) to Freetown that was to lead to the military intervention that toppled the government of President Momoh and changed the course of that nation’s history forever. When Tom seized the gun, he knew he would be under treasonable suspicion, not least by his superiors, and in particular the Commanding Officer (CO) of the Cobra Battalion. To preempt this, Tom ordered his men to arrest his CO, tie him up, and throw him into the truck to which the AA gun had been mounted. (Photo: 2nd Lieutenant Nyuma, as Secretary of State, East, meeting the people of Kenema just after the NPRC coup, May 1992. From the collections of Patrick S. Bernard)

With that done, Tom and his soldiers started the dangerous trip to Freetown. They avoided major roads by using secondary ones, when available. Of course, there are not that many options of secondary roads when traveling from Pujehun/Zimmi to Bo and to Freetown. But Tom had done prior work. That is, many months before the coup, he had undertaken reconnaissance missions by traveling through secondary roads that would take him from Zimmi to Freetown, and back again without using the main roads. In fact, he had discovered during those trial runs that he could travel from Pujehun to Mile 91 without ever having to go through the Pujehun-Bo-Taiama-Mile 91-Freetown primary road. Obviously, going through Bo was a no brainer because moving an AA gun through the town, which by this time had a visible presence of soldiers, would have raised instant suspicion, if not their immediate arrest. They would not even have reached Bo had they attempted to go though that route because there were military checkpoints between Pujehun and Bo. Before they left Pujehun they picked up other soldiers, including his very trusted comrade, Lieutenant Sahr Sandy, at other posts around Pujehun. Earlier that day, Tom had released some of his soldiers, now dressed in civilian attire, who had traveled to strategic points (Bo, Mile 91, Masiaka, etc.) to monitor what the military movement was along the Freetown-Bo highway.

Just after they took off and realizing that there was no turning back now, Tom explained to his CO that they were heading to Freetown to overthrow the APC government. He told him these two options: Either to execute him there in Pujehun, so that he could not contact the military hierarchy about Tom’s seizure of the gun. Or take him along with the coupists to Freetown. Tom had ruled out the first option because, as he told his CO, he would rather kill himself than harm his commander, for whom he had the greatest respect and utmost loyalty. He explained that he knew his commander would not approve of their action and why he had him tied and thrown into the truck. In case they were busted, he told him, he would be the first to tell any one that the CO had absolutely nothing to do with their coup plan and the reason he was tied and, against his will, thrown into the truck and brought along.

Lieutenant Tom Nyuma, giving updates about the rebel war just before the first anniversary of the NPRC, April 1993. From the collections of Patrick S. Bernard

The trip along the secondary roads from Zimmi to around Mile 91 was not menacing, and they evaded any overt suspicion. When they arrived at Mile 91, instead of taking the Mile 91-Masiaka-Freetown highway, the coupists used another secondary route that runs from Mile 91 via Yonibana to Masiaka. But it was the stretch from Masiaka to Freetown that was to prove the most dangerous part of the trip. Why? The stretch has hardly any secondary roads. That the coup succeeded was fortuitous—all coups succeed because of this element of luck. But it was also due to the smart thinking by Tom that they were not intercepted along this dangerous stretch. In fact, they nearly were. And this is how it could have happened, but how it did not.

A missing AA gun was a matter of the gravest concern to the military and political leadership in Freetown and at Daru, where the overall Commander of the war in Sierra Leone, Lieutenant-Colonel Yayah Kanu, was based. And the failure to communicate with the CO in Pujehun who should be in control, and provide instant feedback about the whereabouts, of this weapon was even more troubling. The Military Signals unit at Wilberforce in Freetown had tried repeatedly on April 28 to contact the CO, but to no avail. Signals had also been informed that the AA gun was missing, and with it some young officers, including Tom, from their positions. Yayah Kanu was contacted at Daru, but he too could not tell the whereabouts of the gun, his CO at Pujehun, and the missing officers. Kanu was then ordered to travel to Pujehun immediately to take control of things. He did travel, but he could not find the gun or the commander or make contact with the young officers. While in Pujehun, Kanu was informed that some young officers under his command in Kailahun had also abandoned their positions and gone missing. He was then ordered to promptly report to Freetown. (That was why Yayah Kanu was in Freetown on the day of the coup. Also, that explained why when Kanu gave his first interview to the BBC and said that he did not know about a coup and was not part of one, he was absolutely correct.) By this time, the government had informed the Inspector-General of Police, Bambay Kamara, about the situation in Pujehun. Bambay was ordered to dispatch a counter-coup unit to Pujehun to forestall any attempt at a coup. This unit did not come from the military but from the Police’s Special Security Division (SSD) under Bambay’s command.

By this time, the coupists had already passed Mile 91 and were on the Yonibana-Masiaka road.

Tom and his men were not intercepted by the counter-coup unit, or caught-up with by Yayah Kanu who was on his way at lightening speed to Freetown that night for this reason: Tom knew of a very rugged path (wide enough to allow a military truck to go through) that ran parallel with the Masiaka road for about fifteen miles. He opted to use that path rather than to brave using the main road. But one other vital reason he decided to take that route was when he realized they were ahead of the time they must reach Freetown. At the pace they were going, they could have arrived in the city when people were still in the streets and thereby raised suspicion. Thus, he thought they should slow down and take a rest. But resting with an AA gun along the Masiaka-Freetown highway was a definite no. This move was to prove very crucial. Because twenty minutes after they were into that path, the counter-coup unit from Freetown zoomed passed Masiaka heading to Pujehun. So, while the government and the military leaders were of the belief that the AA gun and the missing officers were around Pujehun, Tom and his comrades were already about forty miles to Freetown.

They arrived in the environs of Freetown around 5 a.m. on April 29. Tom ordered the AA gun stationed at Ferry Junction at about 6:00 a.m. for these strategic reasons: to forestall any military movements from Bengeuma Barracks in Waterloo or from the Lungi Garrison across the estuary from entering the city. Obviously, an AA gun could not have ensured the success of the coup. Also, Tom and his men did not travel to Freetown with overwhelming force that could topple the government. But the moves Tom made when they arrived in Freetown were the most strategic of all. Before he ordered his men to fire the AA gun at about 7:45 a.m., the first gunshots that Freetonians heard that morning, Tom had earlier led some of his men to (1) State House and taken it over, and (2) to the ECOMOG unit that was based close to State House at Tower Hill and disarmed it and informed the unit commander that ECOMOG should not interfere into what was happening in the country because it was an internal matter. But it was the move for State House that guaranteed the success of the coup. Why?

State House was the most heavily armed fortress in Sierra Leone on that day, and had been that way for some time since the rebel war began. State House had more weapons in stock than any military location fighting the war, or all the military barracks in Freetown combined, at that time. In fact, that was why the NPRC coup was unusual—the coupists did not go for military barracks and their arsenal or for any military installation, as is the norm in military coups in Africa. Tom knew about the State House arsenal; in fact he had seen the stockpile when he would, as I have stated earlier, come to pick up supplies authorized by President Momoh. Thus, Tom’s sole aim the moment they arrived in Freetown that morning was to take possession of that arsenal. And once they did, they knew that there was no way Momoh was going to fight back. In fact, it was only after he was sure that they had taken over State House and were in control of the stockpile that Tom ordered the AA gun to be fired. Thus, the success of the coup. Well, almost.

Because Momoh did attempt to fight back. First. As the firing from State House intensified with the coupists firmly lodged in it that morning (having been now joined by some of the other missing officers who were later to become the NPRC core), a line of communication was later opened and Yayah Kanu was told by the government to coordinate it. He made contacts with some of the coupists and they started talking. SAJ Musa was the spokesman for the coupists. Their “negotiations” continued up to about noon, when there was mention of food—the coupists had hardly eaten since they left Zimmi. They were invited to come over at The Paramount Hotel where lunch had been ordered. The hotel is just opposite State House. The coupists, hungry and exhausted, thought it a reasonable offer. But they were soon tipped that the invitation was a trap. Information had reached them that armed plainclothes soldiers or SSDs had been seen entering the hotel from the back through the Soldier Street or Fort Street end. The “lunch” invitation, therefore, was to lure them into the hotel, and once in there, they would be confronted by these plainclothes officers, disarmed and arrested. This information resulted in some of the most intense barrage of gunfire that day. SAJ (or another one of the coupists) ordered that any soldier who attempted to cross over to the hotel would have his head blown off. The coupists fired at the Hotel and demanded occupants to leave immediately. They took it over. And that was how that landmark hotel ceased being a hotel on April 29, 1992. The NPRC was later to convert it into a military structure. It also explains the reason the hotel is the Headquarters of the Ministry of Defence of Sierra Leone today. The communication with Kanu was annulled, and his contact with the coupists was irreparably damaged. Meanwhile, a division of the SSD from Jui had been ordered by Bambay to proceed to the vicinity of State House and The Paramount Hotel. But they were stopped and disarmed by the soldiers with the AA gun at Ferry Junction. (Yayah Kanu and Bambay Kamara, and others, were to be later executed about eight months into NPRC rule after being dubiously accused of “planning” a coup while they were in prison.)

Second. Momoh had asked President Lansana Conte of Guinea to intervene. And he nearly did. Had that occurred, there would have been a bloodbath in Freetown. From the moment the government knew that this was not just a “protest” by “disgruntled soldiers”, it changed this narrative to: Freetown, and Sierra Leone as whole, had been attacked from the outside by Charles Taylor’s rebels and those of Foday Sankoh. With this version, Momoh asked Conte to trigger the security pact between the two countries. Among many other things, the pact states that if one country is attacked from the outside, the other should intervene immediately. Believing what Momoh had told him that Freetown had indeed been attacked by Taylor (no leader in West Africa wanted Taylor in control of Freetown, which was ECOMOG’s headquarters), Conte mobilized a brigade of the Guinean Military and ordered them to proceed to Freetown. Information was that they had already crossed into Sierra Leone territory in Kambia District and headed to Freetown via Port Loko when they were halted by ECOMOG through the intervention of the Nigerian Head of State, Ibrahim Babangida, who had already been informed by the ECOMOG Commander in Freetown that what was happening in the city of Sierra Leone was an internal matter and not a take-over by Taylor and Sankoh. Thus, with Babangida’s intervention, Conte was advised to withdraw his troops. Babangida and Conte then started strategizing Momoh’s surrender because Babangida had also been informed that what was happening in Freetown was a coup. Babangida was to prove the most crucial asset for the NPRC in its first few months.

At about 2:00 p.m. with Sierra Leoneans (minus the coupists) not knowing what was happening except for the brief information from Momoh’s interview heard over the BBC that “disgruntled soldiers” had decided to “disturb the peace” in Freetown, FBC campus was tense with speculations among scattered groups of students, lecturers and workers. At some point, I spotted Tom’s father approaching me. He indicated that he wanted to talk to me in private. I thought he was going to tell me that he could not get his workers to come do the repairs at my FBC flat which he was overseeing. However, the moment we were together I saw that his hands were shaking and his eyes swelling with tears. He asked me in Krio in a trembling voice, “Yu yeri enitin but yu borbor?” (“Have you heard anything about your boy”). Pa Joe always referred to Tom as my “boy.” I said no. He then told me that one of his workers who had made it from Freetown to campus had seen Tom at State House leading soldiers that morning. I froze, as I recalled to myself what Tom had told me years back about his “destiny.” But I did not let Pa Joe notice my shock and paralyzing fear. As a concerned father who knew that his son had endangered his life by coming to take part in this “protest” (because that was the news we had heard), Pa Joe was in tears now and pleaded if it would be possible for me to get to Freetown to talk Tom out of what Pa Joe called “this nonsense.” (Pa Joe believed that Tom used to listen to me more than anybody else, including him). To calm him down, I said I would and I was going to find a ride to Freetown. Of course, there was no way I was going to Freetown given what was happening. I expected the worse, and I knew where Pa Joe’s deep fear was coming from. We both knew, although we did not say it to each other, that after all this “protest” was over, all the soldiers involved in it would be arrested and accused of attempting a coup. This was subtly suggested, we believed, in Momoh’s euphemism of “disturbing the peace,” which could have meant a coup or a mutiny.

It was a day after the coup, about 3:00 a.m., that I heard multiple taps on my bedroom window. I was scared, because Freetown was still filled with rumors that a counter coup was in the offing. The taps continued, and then I recognized the gruff voice of Tom saying, “Brother Bernard, Brother Bernard, opin di doe, na Tom” (“Open the door, it is Tom”). Tom never called me by my first name, nor put “Mr.” before my last name. I was always “Brother Bernard” to him, an honorific that stuck after I (and Mahdieu Savage) had recruited him to become a member of the Pan African Union (PANAFU) before he became a soldier. I opened the door, thinking that he had come to gloat, but no. He entered my flat looking energetic but somber and reflective with his eyes showing deep strains of sleeplessness. He told me that they were “mopping” up and “stabilizing” the situation and he had not slept in two days. He was at my place briefly he said because he wanted me to know certain facts just in case he was killed. He confirmed the possibility of a counter coup where he would be the primary target. He also said he would be traveling to the war front in the next day or two to calm restless soldiers who were concerned about the coup and the war, and thought that he could be ambushed and killed while there. He mentioned the killing of Lt. Sandy (whom I had never met) multiple times, and I could tell that he was devastated and traumatized by his killing. (I believed it was the killing of Sandy that made him feel vulnerable.) He narrated that night a substantial part of what I have written here. Obviously, this is Tom’s version (although a very senior NPRC member confirmed almost all what Tom had told me two weeks after the coup). There may other versions out there.

Over the years, Tom always said we should collaborate to write a book about the NPRC. When he was in the US, he used to visit me; during one such visit he came along with one of his former comrades to talk about the book. He always wanted his role in the making of the NPRC coup to be known by all Sierra Leoneans. It is unfortunate that he did not live to realize his aims and read this story in print.

This tribute is about Tom and what he told me of what happened on April 29, 1992 and not about NPRC rule (that is another narrative). Tom’s actions during the rule of the NPRC would be forever filled with controversies. His short and controversial political career, in particular when in 2010 he left the SLPP to join the APC, whose toppling, had it failed, would have cost him his life, dogged his brief tenure as a politician. What will be indisputable, however, is his bravery and brilliance as a soldier and his commitment to make sure that the RUF rebels did not rule Sierra Leone. The military strategies and tactics that he deployed, first, to outwit the rebels, and second, to overthrow an APC government that was coup-free for close to 30 years despite the many attempts, real or framed, that had been made to topple it, will make Tom, as I have said, one of the most ingenious, audacious, and adventurous soldiers in the history of the Sierra Leone military. And he achieved this feat when he was just twenty years old.

Whatever our views and opinions about him, Tom Nyuma changed the history of Sierra Leone on April 29, 1992. And no Sierra Leonean can deny this fact. No history of Sierra Leone after that date will be complete without reference to the actions of “Ranger.”

Adieu, Ranger!

By Patrick S. Bernard

Stay with Sierra Express Media, for your trusted place in news!

© 2014, https:. All rights reserved.