Two Sierra Leoneans vying for ICC prosecutor job

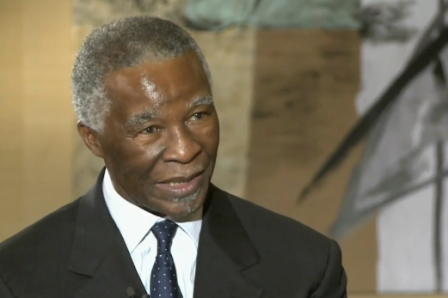

As the International Criminal Court gears up to elect six judges and a new prosecutor, observers are warning that political rather than merit-based considerations could govern the evaluation of candidates. (Photo: current prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo)

The nomination period for the elections – which will determine replacements for six of the ICC’s judges and its chief prosecutor, the court’s most visible position – begins next month, with voting scheduled for December. But there are already signs that states parties to the Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding treaty, will politicise the process.

At a January summit, the African Union suggested it would advocate for an African prosecutor, issuing a declaration that noted the “significant participation” of African countries in the court, as well as “the fact that there is no African heading any of the main organs of the institution.”

All of the ICC’s active cases involve crimes committed in Africa, a fact that has exposed the court to criticism from those looking to brand it a tool of the West. At the same time, Africa boasts more states parties to the Rome Statute than any other region.

Though the AU did not make an explicit push for a particular candidate, resolving to revisit the matter at a summit scheduled to begin Jun. 23, observers said it was no secret the body wanted an African to fill the shoes of current prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo.

“It’s clear that they have a strong preference for an African candidate,” said Param-Preet Singh, senior counsel for the International Justice Program at Human Rights Watch, which has called for selections to be made on the basis of merit. “But he or she shouldn’t be chosen as a prosecutor simply because he or she comes from that region. That shouldn’t be the driving force.”

William Pace, convenor of the Coalition for the International Criminal Court, a group of more than 2,500 civil society organisations, said attempts to exert political pressure would likely not be confined to the election of a new prosecutor.

Choosing judges

The Rome Statute requires that candidates for the bench – the ICC has a total of 18 judges – be “of high moral character, impartiality and integrity” and have “established competence” in criminal law or “relevant areas of international law.” When voting, states parties are instructed to take into account distribution requirements for gender, geography and legal systems (criminal or international).

In a May 18 letter addressed to the foreign ministers of all states parties, HRW noted that these requirements left “a significant degree of latitude” in selecting judges, and called for three other criteria to be considered: substantial practical experience in criminal trials; capacity and willingness to meet the demands of adjudicating cases over a nine-year term; and commitment to ongoing training.

Singh said that while these criteria might seem “obvious,” they have not always been taken into account. She said it was particularly important that they be considered this time around because four of the outgoing six judges have been serving in the Trial Division, while a fifth has been serving in both the Pre-Trial and Trial Divisions.

“These are the judges who know how to adjudicate cases, and they’re leaving,” she said.

Though the Rome Statute provides for an advisory panel on judicial elections, it will not be established until December 2011 – too late to evaluate this year’s nominations.

The ICC did not respond to a request for comment as to why the panel wasn’t established earlier, but Pace said the delay suggested that choosing the most qualified candidates was not a particularly high priority for states parties. In lieu of the ICC panel, the CICC has formed an independent panel of international law experts — some of whom have experience at ad hoc tribunals — to evaluate judicial candidates.

Historically, he said, the handling of elections for global bodies has been “extremely mediocre,” with “crude political considerations” dominating the process.

One of the potential long-term dangers of politicised elections at the ICC is that they could politicise the actual work of the court, Pace said. In the election for prosecutor, for instance, he said some countries could lend support to a candidate on the condition that he or she agree not to conduct investigations on their soil.

Brigid Inder, executive director of Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice, took issue with the notion that an AU endorsement would be inappropriate. “From our perspective the politicisation of the process isn’t coming from the African states, but from others who are saying if the Africans put up a candidate it will politicise the election,” she said.

“The issue isn’t if the AU endorses a candidate. The issue is why others are working hard to prevent the AU from endorsing a candidate and therefore ensuring there isn’t a strong African candidate who could viably contest the election for the next chief prosecutor of the ICC.”

Both Singh and Pace said the elections come at a time of rising prominence for the ICC, as evidenced by the U.N. Security Council’s unanimous referral of the Libya situation to the court in February.

Pace noted that as the various ad hoc tribunals – for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, for instance – wind down, the ICC is becoming “the primary if not the only international criminal court for the most terrible crimes in international law.”

The court must navigate this transitional period, he added, while undergoing an almost complete change in its leadership over the next year: along with the prosecutor and the six judges, elections will also be held in December for a new president and two vice presidents of the Assembly of States Parties; six members of the Committee on Budget and Finance; and a 21-member “Bureau”, the ASP’s executive committee. In early 2012, elections will be held for the ICC’s president and two vice presidents.

Replacing Moreno-Ocampo

The election of judges will take gender, geography and other considerations into account to produce a representative bench. There are no such requirements to consider when choosing the chief prosecutor and deputy prosecutors: the Rome Statute states only that they “shall be persons of high moral character, be highly competent and have extensive practical experience in the prosecution or trial of criminal cases.”

As such, Pace said any push for a specifically African prosecutor has no grounding in the statute. “There’s no requirement that there should be regional rotation on the position of the prosecutor. There’s no requirement that the prosecutor should come from the region where most of the situations that the court is dealing with are occurring,” he said.

Pace noted, though, that some of the potential candidates being floated for endorsement by the AU – including Ocampo’s Gambian deputy, Fatou Bensouda, who Pace termed “definitely a frontrunner candidate” – are “very highly qualified.”

Referring to Bensouda, Inder said, “It is not lost on many states, institutions and NGOs following this election, that the leading African candidate to date is a woman and people are wondering whether this is also a factor in the additional efforts being made this time around to prevent the AU from endorsing a candidate.” Other African candidates in contention are the South African ICTR Deputy Prosecutor, Bonjani Majola, Botswana’s Attorney-General Dr Athalia Molokomme and two Sierra Leoneans, Transport Minister and former Deputy Foreign Minister, Vandi Chidi Minah and former Special Court Appellate Counsel and Anti-Corruption Commissioner, Abdul Tejan-Cole. The latter is quoted to have said he is not interested in the job.

The court has established a five-person search committee tasked with producing a shortlist of at least three candidates for chief prosecutor. During the December elections, the Rome Statute stipulates 114 states parties should attempt to reach a consensus decision. Failing that, secret ballot voting will occur.

In a May 18 letter to the search committee, HRW identified a range of desirable qualities for prosecutor candidates. Some of these – such as “demonstrated experience in working with other bodies or agencies” and “demonstrated experience in communicating effectively to a wide variety of constituencies” – underscored the group’s belief that as the ICC assumes a greater role on the global stage, the prosecutor “will likely be even more closely scrutinised and subject to criticism, both legitimate and unjustified.”

Singh emphasised that the mounting pressure on the court to start completing cases – the first trial, that of Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga, is scheduled to enter closing arguments in August – will leave the new prosecutor with little room for error.

“There’s been an emphasis placed on the importance of judicial institutions to deliver,” Singh said.

“That makes it more important that there’s someone at the helm who has the skills to meet the challenges that have emerged and will continue to intensify.”

Michael Vandy

Stay with Sierra Express Media, for your trusted place in news!

© 2011, https:. All rights reserved.