Changing the mindset around blindness

FREETOWN, 4 November 2011 (IRIN) – In Sierra Leone misconceptions about blindness are widespread, and people often blame blindness and other disabilities on witchcraft, but local and international work is being done to reduce stigma and open up opportunities, according to campaigners. (Photo: A blind student carrying her braille boolk, photo Helen Keller Institution)

“The less educated public, especially those still living in remote rural communities, believes in witchcraft, and many unusual illnesses or afflictions can be blamed on it,” said Mary Hodges, Sierra Leone’s country director for NGO Helen Keller International (HKI). Blindness is also sometimes viewed as punishment and an indication that the afflicted person or their ancestors were at fault.

Saidu Banguru, a blind advocate working with HKI, said many people avoid the blind as they believe blindness is contagious.

Blind people are also often excluded from essential services. A 2009 study conducted in urban areas of the country by international NGO Leonard Cheshire Disability, found disabled people had less access to education, health care and employment than other citizens.

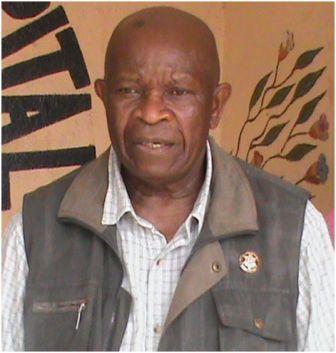

“People with disabilities are not recognized – in schools [blind students] aren’t expected to excel, and in the workplace people don’t believe that blind people can deliver results,” said Thomas Alieu, founder of an adult education centre for the blind, who became blind after a bout of measles when he was five years old.

According to HKI figures, 71,825 people (1.3 percent of the population) in Sierra Leone are completely blind, mostly due to measles coupled with vitamin A deficiency, cataracts, river blindness, trachoma and injuries sustained in the civil war. Measles usually strikes in childhood, river blindness tends to affect people later in life, and trachoma in old age.

HKI started working in Sierra Leone in 2002, initially focusing on preventing blindness, but has since expanded its programmes to include advocacy for the blind. Hodges said progress was being made in fighting stigma, and pointed to rapid change in Sierra Leone after the civil war ended in 2002.

Changing attitudes through education

Increased international investment and growing urbanization have also contributed to a more inclusive approach. “People have far greater access to [things like] school, radio and TV, and beliefs and attitudes are changing rapidly,” Hodges said.

HKI runs a radio show to educate the public and reduce stigma towards the blind. Banguru, the show’s host, brings in experts to discuss issues around blindness. He said the show has received calls from listeners saying they now have a better idea of how to interact with blind people.

Besides advocacy and programmes to prevent blindness, HKI also directly supports Sierra Leone’s five provincial schools for blind children, providing textbooks in Braille and supporting refurbishment of the infrastructure.

There are also plans to support specialist teacher training for the visually impaired, but Hodges said it is unclear what percentage of blind children the schools are able to reach as there are no accurate figures.

Alieu said providing education was part of the battle against stigma, and once blind people showed what they were capable of it altered other people’s perceptions of them. Provision should be made for adults unable to attend specialist schools when they were children, or who became blind in adulthood, which is why he had opened the Education Centre for the Blind in his Freetown home in 2000, catering for adults, as well as children and youths.

Kamada Conteh told IRIN that since he started studying at the centre he is “respected at home as well as on the street”. Another student, Bai Kamara, 20, said before enrolling at the centre he spent his days begging, but now feels he can “achieve something”, and hopes one day to attend university.

Alieu said former students are now working as teachers in schools for the blind as well as conventional schools, and one former student has a job at HKI. The centre currently caters for 100 students and receives funding from the government and NGOs.

Government action

A Disability Act to ban discrimination and open up education and employment opportunities to disabled people, including the blind, was passed by Sierra Leone’s parliament in March 2011, but the acting Minister of Social Welfare, Gender and Children’s Affairs, Rosaline Sankoh, said activities were on hold due to the “tight budget”.

The formation of a Disability Commission, planned for October, has been postponed until later in the year. She said the government is hoping to obtain funding from international donors to implement the Act.

Patricia Mansaray, the disability officer at the ministry of social welfare, gender and children’s affairs, was more optimistic, noting increased political will. “Government is turning their attention to disability issues,” she said, adding that this year the government allocated 600 million Leones (US$137,000) to disability services – more than in previous years – and she expected the amount to increase again in 2012.

At present there is no distinction between services for the blind and for other disabilities, said Mansaray, and further work is necessary to establish specific needs – the only studies on disability in Sierra Leone were done by NGOs. “A survey is one of the things we need to do, to [find out] where blind people are [and] what they do.”

IRIN

Stay with Sierra Express Media, for your trusted place in news!

© 2011, https:. All rights reserved.