Why Aminata did not die in vain

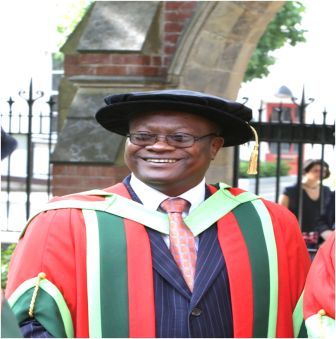

The death of Aminata Marah in childbirth was a wake-up call for Dr Samuel A.S. Kargbo. Sierra Leone’s reproductive health minister tells of the steps he has taken to try to ensure no such tragedy happens again. (Dr Samuel A.S. Kargbo at a staff meeting in Freetown.) Photo credit: Dominic Chavez

Two days ago, new figures emerged showing a 35% drop in maternal mortality worldwide, with surprising progress made in many developing countries. Dr Samuel A.S. Kargbo, Director of the Reproductive and Child Health program for the Ministry of Health and Sanitation in Sierra Leone, who explains how one tragic death moved him to instigate major reforms in his country which are saving many other women’s lives.

Freetown, Sierra Leone

Aminata Marah arrived, pregnant and bleeding, in a hammock carried by four men. They had carried her for three days – she had been in labor for four – before arriving in Kabala, in northern Sierra Leone. I was working as a general practitioner at the time, one of the few doctors in Sierra Leone and the only one in Kabala. I knew what her family didn’t: she had an obstructed pregnancy and she needed a C-section. She had needed a C-section three days ago.

While preparing for an urgent transfusion to replace the blood she had lost on the way, we rushed her to the operating theater. Soon after, a nurse told me she was dying.

This woman received the best care possible in Sierra Leone at the time. She was in a hospital. She was about to receive a blood transfusion. She made it into an operating room. And yet, she died.

That was May, 2006. It was my wake up call.

Today this would not happen in Kabala. Since then, we started an ambulance service. We worked with the community to build a savings fund that gives loans to those in need of urgent care. We got a solar-powered refrigerator, so that we could store blood for the first time. And the paramount chiefs in the area handed down a decree: Every mother must give birth in a clinical setting. If there is one thing I’ve learned from my time in Kabala, it is that when there are complications, women who give birth at home die.

Since this decree, there have been no maternal deaths for three years in some chiefdoms in the Kabala region. In a district of 40,000 people, safe births are becoming the norm.

That is not the story you are used to hearing from Sierra Leone. To readers in Europe or the United States, we are a country at the other end of the world, one that just emerged from a devastating civil war. Perhaps you’ve come to expect only stories of poverty, corruption, and hopelessness.

In a way, those stories do reflect some of our problems. For instance, we have no basic emergency obstetric care center – not one in a country of 6 million. The United Nations recommends that countries have four such centers for every 500,000 people.

But those stories don’t reflect that we are making progress, often against great odds. In 2001, the World Health Organization estimated that 2,100 women died for every 100,000 live births; a household survey last year dropped that estimate to 857 women dying. That rate is still among the highest in the world, but we are working on plans that we expect will dramatically reduce the current death toll.

Today, as the head of reproductive health programs at the Ministry of Health and Sanitation, my challenge is to replicate the model we built in Kabala across Sierra Leone. We know what we have to do. Saving the lives of women and children means more funding, staff, and supplies.

Some of what we need is small – with just 30 solar-powered refrigerators we could open enough blood banks to begin to address our nation’s shortage. Other needs are greater – we must train 150 to 200 midwives each year to keep up with demand and attrition. Right now, we train only 30 annually.

We have long had generous donors. But this past year, we’ve begun to receive a new kind of assistance as well. Experts from the U.S.-based Ministerial Leadership Initiative for Global Health at the Aspen Institute and the U.K.’s Tony Blair’s Africa Governance Initiative are helping us build skills inside the Health Ministry. With a stronger Ministry, we know we can make serious progress.

They are asking us what we need – not telling us what to do, as others have in the past. This makes a huge difference. We hope that other donors follow this same path – looking to Health Ministries in Sierra Leone and in other countries to take the lead on what is best for their nations. We see the problems every day. We need outside help to solve them.

Only with more support to Health Ministries – not just funding — can we begin to address the problem on a national scale.

Aminata’s death was my wake up call. Now let it be yours.

Stay with Sierra Express Media, for your trusted place in news!

© 2010, https:. All rights reserved.