Resource Wealth and Development

(A Note for a panel discussion on launch of Paradoxes of History and Memory in Contemporary Sierra Leone; edited by Sylvia Ojukutu-Macauley and Ismail Rashid; Lexington Books, 2013)

One of the big challenges I often face when trying to understand Sierra Leone’s contemporary history is how little there is of scholarly work that connects past and present efforts in generating economic, social and political development.

There is a lot of historical and contemporary work on various aspects of development. However, much of this work is fragmented. We lack a grand, systematically structured narrative that draws on the work of early writers, who focused on the 1960s, to tell the story of multiple shocks on, and revival of, the present economy, society and politics.

This lacuna has led to the unfortunate situation where popular understanding of critical developments, especially in our politics, is not informed by expert opinion or archival knowledge. There is much amnesia and revisionism, including rehabilitation and even glorification of actors who may have laid the foundations for our underdevelopment.

Efforts to rehabilitate or glorify discredited leaders owe much to the fact that most of today’s youths cannot easily connect what they currently experience to events in the first two decades of independence; and there are very few, if any, authoritative and easily accessible books they can read to make these connections.

My contribution to the book, Paradoxes of History and Memory in Post-Colonial Sierra Leone, which is the basis for this panel, is based on a keynote speech that I gave at a policy dialogue organized by the UN Institute for Development and Economic Planning based in Dakar and Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Finance as part of the celebrations to mark Sierra Leone’s fiftieth independence anniversary.

I was concerned with three issues that still confront us in our efforts at nation-building:

–how to harness our abundant natural resources for economic growth and transformation that will improve national wellbeing;

–how to rebuild and expand our highly degraded human capital;

–and how to rework our politics to make it serve an agenda of economic and social transformation.

Because of time constraints, I will limit my comments to the resource wealth dimension of the problem of nation-building.

Indeed, I would like to suggest that our failure to properly manage our natural resources contributed substantially to the degradation of our human capital and the series of crises that ultimately led to our war and collapse of institutions.

Three issues stand out in discussions on resource management:

–ability of the state to capture a large part of the resource rent;

–ensuring that the agricultural and manufacturing sectors of the economy are not disadvantaged when formulating macroeconomic policies—in other words avoiding overvalued exchange rates and large budget deficits;

–spreading the benefits of the resource rent, including savings for future generations, and preventing environmental degradation.

Historical developments

Sierra Leone, like most resource-rich countries in the 1960s, tried to use its resource rents to support industrialization. Places where such strategies have been successful have involved a strong state project that either nurtures a national entrepreneurial class to lead the industrialization process, or attracted foreign direct investors and linked local capital to such investors. Whatever the strategy chosen, no successful industrialization has taken place without strong state support for local capital.

In Sierra Leone, diamond extraction and exportation was the dominant form of wealth generation in the early period of independence. There were two types of diamond extraction.

The first was small and medium scale mining, in which the granting of diamond licenses to domestic dealers played a key role. Many of the commercial and service activities in the big towns and capital city were fuelled by the proceeds from diamonds. A strategy that seeks to encourage local business groups to upgrade from commercial to manufacturing activities requires, therefore, effective management of the process of granting licenses to small and medium scale dealers.

The second type of diamond extraction was industrial large scale mining, involving the participation of foreign capital. State capture of rents from this sector is important in supporting human capital formation, infrastructural development, import-substitution industrialization and diversification of the economy.

Unfortunately, the state failed to capture much of the resource rent or cultivate indigenous African entrepreneurs as partners in the lucrative mining sector that would have formed a foundation for investment in other sectors of the economy. Instead, a pernicious process of informalization was encouraged that created massive leakage of the diamond revenue from the state sector; and Lebanese businessmen, who were perceived as apolitical, became the state’s partners in the production and sale of our natural resources.

Consider these numbers. In the 1960s, African dealers accounted for 85 percent of diamond licenses, compared to 15 percent for Lebanese business dealers; but by 1973, the Lebanese had become the dominant players, accounting for 78 percent of the licenses and Africans only 22 percent.

In addition, the institutions established during colonial rule and the first decade of independence to manage large scale mining in the resource sector were systematically dismantled after 1973.

—The Sierra Leone Selection Trust, the transnational mining company, was rendered ineffective;

—and the National Diamond Mining Company (NDMC), the state-dominated company, was stripped of its monopoly in carrying out mining operations on its rich diamond deposits and export activities.

—Individuals with strong patronage links with the state (the top players were of Lebanese descent) took control of the mining sector.

By 1980, the NDMC accounted for only 29 percent of legally produced diamonds, compared to 94 percent in 1973. This leakage, when combined with worsening terms of trade for Sierra Leone’s export commodities and hosting of the extravagant OAU conference in 1980, contributed to the state’s fiscal crisis, the inability to fund the limited import-substitution industrialization that had started in the 1960s, the dramatic decline in educational and health provisioning, and the fall in household incomes in the 1980s. All of this happened well before the war of the 1990s.

One may argue that there is nothing wrong with Lebanese dominance of the mining sector if the mineral rents can be used in activities that will lead to a diversification of the economy. To borrow the late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s famous statement when carrying out market reforms in China after the death of Communist leader Mao, “what does it matter whether the cat is black or white as long as it catches the mice?”

Unfortunately, in our case, the pampered “white cat” did not catch any mouse. This was largely because the same state that favoured Lebanese enterprise in the mining sector had a racist citizenship law that discriminated against this key business group. We ended up with the worst possible outcome where the Lebanese were allowed to exploit our resources and make money, but the citizenship laws acted as a disincentive for them to invest the resource rent in local productive sectors on a large scale.

In Malaysia, which is also a multi-ethnic state, even though the Malay were considered indigenous, the citizenship status of the Chinese, who dominated business, was never questioned; and the Chinese collaborated with the Malay (even if as unequal partners) in forming the political coalition that governed the country and advanced the project of economic transformation.

Current developments

Where do we stand today? Some progress has been made since the war to improve natural resource management. The rampant informalization of the 1970s-1990s has been checked. However, huge challenges remain.

Studies suggest that the state is still very far from capturing a large share of the resource rent. This applies to most African resource-rich countries. Part of this is tied to the very generous concessions, in the form of royalties, corporate taxes, value added taxes and import duties, given to mining companies. Despite the renegotiation of mining contracts by the Sierra Leone state, the danger of a few companies monopolizing the resource wealth and providing kickbacks to political and administrative elites for ridiculously high concessions is still real.

Actionaid estimates that the Sierra Leone state lost about $224 million in 2012 largely because of generous tax concessions given to the five largest mining companies and a cement factory; the value of the concessions given to these companies was much higher than the goods and services tax revenue (GST) collected by the National Revenue Authority in 2012; despite a statutory corporate income tax rate of 30%, the big companies succeeded in negotiating customized deals, resulting in one company paying 0 percent rate and another 6 percent; none of the four largest companies pays the statutory 30 percent rate. In Guinea, under Lansana Conte (the country’s previous president), an Israeli company, which bought the mining rights of the Northern part of the rich iron ore deposits at Simandou for $160 million, sold those rights to a Brazilian company for $2.5 billion. In Zambia, an Indian businessman was recently caught on video mocking the Zambian state that although he paid only $25 million for a copper mine, he makes $500 million every year and an extra $1 billion from the mine.

Expert opinion on the extractive sector, as highlighted in the Africa Progress Report of 2013, affirms that the current boom in the prices of mineral resources may turn out to be a super cycle boom comparable to the commodity boom associated with American industrialization in the late 19th century and the boom of the 1940s and 1950s that was linked with the recovery of Europe and Japan. The current super cycle boom is driven by China’s rapid pace of industrialization, which is unlikely to end very soon. Estimates suggest that China’s share of global import of base metals rose from 12 percent in 2000 to 42 percent in 2011. While China’s economic growth may fluctuate and importation of metals such as iron ore may falter periodically, as happened early this year, most projections highlight an overall upward trend, with the country continuing to rely on resources on a massive scale until around 2020.

A super cycle boom may last 10 to 30 years. A consensus is emerging among scholars of extractives that large scale concessions are not necessary to attract mining companies. Studies suggest that it is the quality of infrastructure, the cost of conducting business, a stable macroeconomy and political order that attract foreign investors.

Furthermore, most of the new ore discoveries are located in Africa, with the continent accounting for seven of the ten biggest mining deals in 2012. This gives considerable leverage to African states to strike favourable deals since there are very few alternatives elsewhere that are attractive to mining companies. It may explain why Rio Tinto decided to stick with Guinea, promising new investments of about $20 billion in the Simandou iron ore mines, despite the state’s new resolve to increase its share of mineral revenues by renegotiate all mining contracts signed by Lansana Conte. The Simandou iron ore deposits are reckoned to be the largest in the world, prompting speculation that any company that gains control of them may ultimately dominate the global supply of iron ore.

Mining concessions, of the scale that we have seen in Africa, transfer huge amounts of money to foreign firms, especially in contexts where countries do not have capital gains taxes to recapture some of the gains that arise when prices of commodities go up as they are bound to do in a commodity super cycle.

Let me conclude. Political scientists use history to understand development paths or trajectories, mutually-reinforcing institutions, critical junctures, and institutional change. When one studies the dynamics of resource management in Sierra Leone from a historical perspective, it is not clear that we have been successful in charting a new development path that will usher in a politics of economic and social transformation.

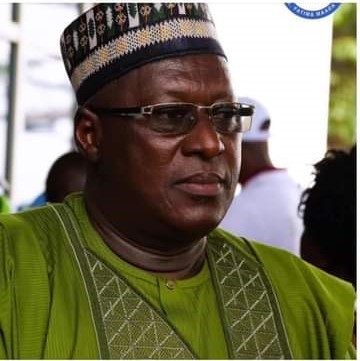

Yusuf Bangura, Department of Political Science, Fourah Bay College 5 June, 2014Stay with Sierra Express Media, for your trusted place in news!

© 2014, https:. All rights reserved.